Skylights: July 2021

July 2021 :

Note: This article may contain outdated information

This article was published in the July 2021 issue of The Skyscraper and likely contains some information that was pertinent only for that month. It is being provided here for historical reference only.

I’d like to introduce what I hope will be a fairly regular feature, by thanking Dave Huestis for his decades of contributions to our newsletter. Last month, Dave announced his retirement from being a monthly contributor, and it is worth noting the significance of his work. I first encountered Dave’s writings during the Halley’s Comet era, when I would read his “Ask the Astronomer” articles in the Woonsocket Call. As I was just beginning to learn about the sky at the time, and knew no one knowledgeable in astronomy, my Dad and I decided to take a trek to try to find Seagrave Observatory one Saturday afternoon. The journey was unsuccessful, and I wouldn’t make my first visit to Seagrave until a decade later, having become a book-learned amateur astronomer, which included Dave’s articles.

When I became editor two years later, it was Dave’s articles that mainly kept The Skyscraper going for many years, when content was light and the average issue was only three pages (page 4 was the address label and directions). Over the decades Dave has diligently covered all manner of happenings in the sky, from the Moon and planets, meteor showers, equinoxes and solstices, sunspots and eclipses. His articles were straightforward and informative, simple to understand, and made astronomy accessible to all, not just those with sophisticated equipment or expertise. Dave also continues to make countless contributions as our historian, including the 75th anniversary book published in 2007, all written by Dave.

Of course, no mention of Dave’s efforts would be complete without mentioning that with Dave’s writing, and Tina’s editing, they made a great team. As a result, their articles were of superb quality and accuracy, and were worthy of publication in a book. In fact, some years after the publication of the 75th anniversary book, Dave informed me that he later found only one error in it, that no one has yet found.

A big thank you to Dave and Tina for the many contributions to Skyscrapers over the years!

Sun, Moon & Planets

Earth reaches aphelion, the farthest point in its orbit around the Sun, on July 5.. At about 6pm EDT, we will be 1.016729 AU (152.1 million km) from the Sun. Compared this with perihelion, when we will be closest, on January 4 at 0.98 33 36 AU (147.1 million km) from the Sun.

While Mars has been visible in our evening sky for the past year, reaching its most recent, and very favorable, opposition in October, this month presents the last time the Red Planet will be clearly visible before it fades into twilight. While it doesn’t present much of a view through a telescope owing to it being nearly opposite the Sun from Earth, it is worth watching throughout the month.

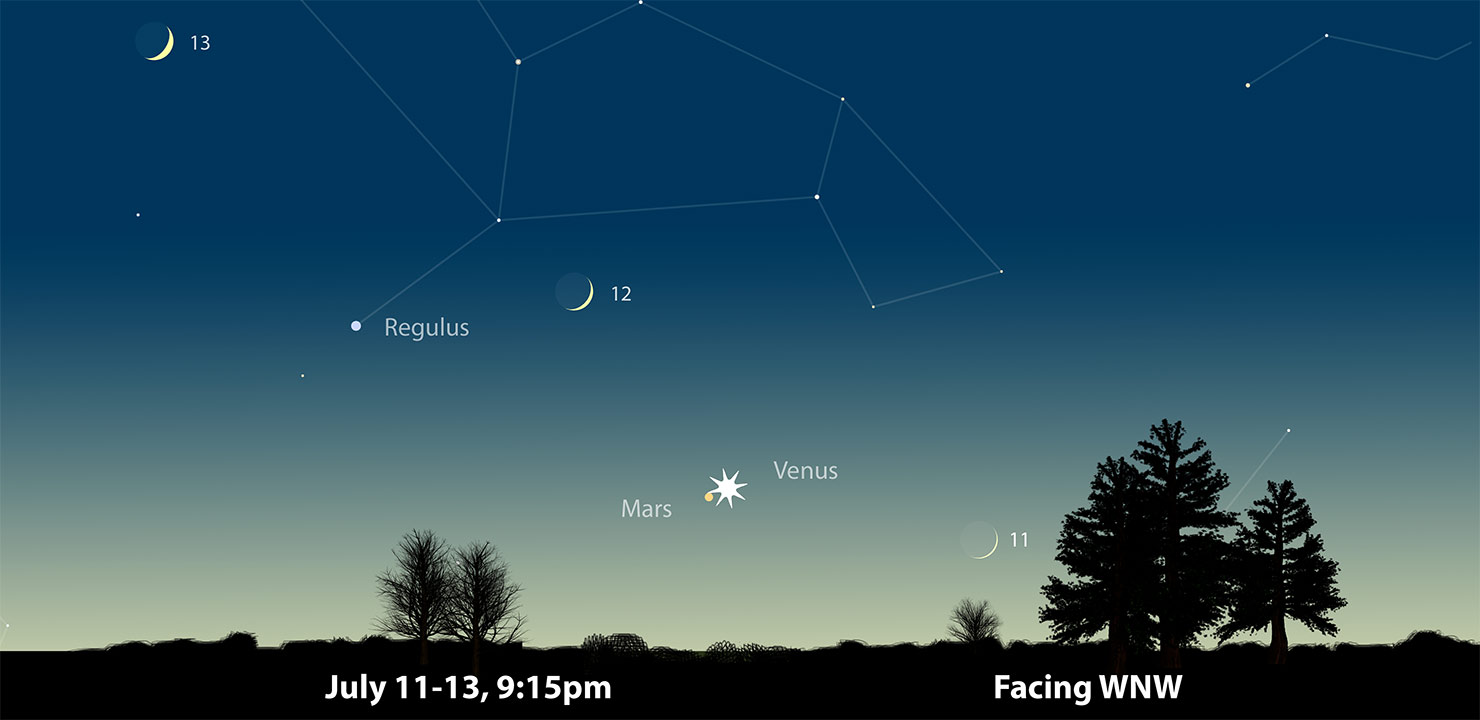

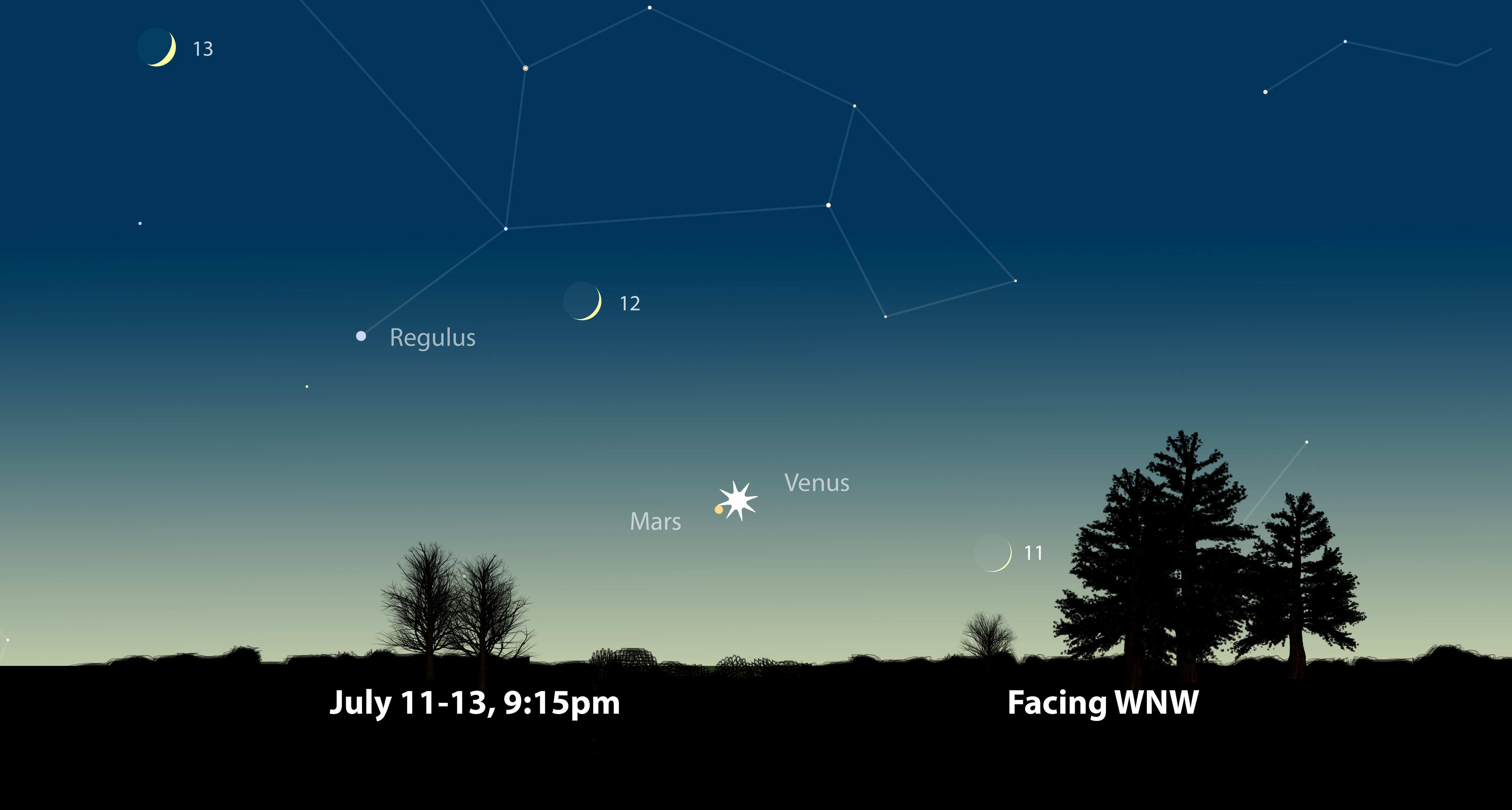

You’ll notice the apparent distance between Venus and Mars closing with each passing night. They begin the month 8° apart and culminate on the 12th & 13th, when Venus and Mars appear just 1/2° apart. At this time, Venus outshines Mars by a factor of 200. Venus is 1.43 AU away and Mars is 2.47 AU away. Additionally, the waxing crescent Moon appears to the west of, then to the east of the pair on the 11th and 12th, respectively.

While you’re watching Venus close in on Mars, you’ll see it pass over the northern portion of the Beehive Cluster (M44) on July 2. Because the stars in the Beehive are rather dim compared to Venus, the best viewing will be about an hour after sunset, when they will be only about 4° above the horizon. If you miss the closest position on the 2nd, they will be fairly close from the 1st through the 4th.

The waxing crescent Moon joins Venus & Mars on July 11th and 12th, and later in the month, Venus, Mars and Regulus in Leo form a dynamic triangle that changes quite drastically. On the 21st, Venus aligns with Regulus, just 1° away, and one of the final notable events of the 2020-2021 apparition of Mars occurs on July 29st, when it passes within 0.6° of Regulus. Such a pairing generally presents a striking view with binoculars or a telescope, especially given that Mars is just 0.5 magnitudes dimmer than Regulus, but because they will be very low on the horizon and struggling to shine through bright twilight, the color contrast of the pair is mostly lost. One aspect that you can look for, however, is noting how Regulus twinkles, and Mars, even at its diminutive 3.9 arcsecond apparent diameter, shines relatively constant--one of the distinguishing features that helps to visually identify planets among the stars.

Saturn rises just after 22:00 EDT in early July, and just before 20:00 by the end of the month, as it nears opposition on August 2. Now that Saturn is high enough to observe with a telescope fairly early in the evening, you may notice that its ring plane angle is less than it was last year. Although the ring plane angle as seen from Earth can vary slightly compared to that relative to the Sun, the difference is relatively small, and observing the angle of the rings is a good indicator of the progress of seasons on the ringed planet, which takes 29.5 years to complete one orbit. Each season lasts just over 7⅓ years, and we’re currently viewing Saturn’s northern hemisphere summer. As the ring plane angle continues to close, we watch Saturn reach its equinox, The ring angle will be narrowing until the next equinox in 2025, when they will appear edge-on, after which we will be looking at Saturn’s southern hemisphere

Jupiter rises at 23:00 at the beginning of July and at 21:00 at the end of the month. Jupiter currently resides in Aquarius and is the apex of an isosceles triangle with Saturn and Fomalhaut (Alpha Piscis Austrinus) that is 20°x30°, pointing towards the Great Square. The just-past-Full Moon joins the gas giants beginning on July 24th, when it rises just 6° below Saturn, and just 4.5° south of Jupiter the following night..

The best opportunity to see Mercury in July is during the first half of the month, when it rises over an hour before the Sun. Mercury reaches its maximum elongation, 22° west, on the 4th. Watching Mercury with a telescope during this time reveals its rapidly changing phase, from a 19% crescent on July 1st, through a 82% gibbous by the 16th. While observing Mercury with binoculars or a telescope, you’ll see it pass two stars in Gemini, magnitude 3.3 Propus (Eta Geminorum) on the 14th, followed by magnitude 2.9 Tejat (Mu Geminorum) on the 15th.

The Full Buck Moon occurs on July 23rd, and for us in New England, it rises completely above the southeastern horizon just a few minutes past sunset, which makes for dramatic views and photos. This full Moon is notable for being substantially south of the ecliptic at a time when the Moon is already near the southernmost point on the ecliptic. Only June’s full Moon was farther south in true declination, by only about 1.5°. Still, our Full Moon this month will be only 24° above the southern horizon when it transits at 1:01 EDT on the 24th.

This low-cast light of the late-July Moon can create a very serene and immersive setting, especially if one can remove oneself from distracting artificial light and sound. In the wooded areas, this is the time of year that the katydids begin to appear, becoming our nighttime companions with their intermittent chirping, and if you’re out near a field, the abundant sound of crickets and the sporadic flash of a late-season firefly add to the experience. And don’t forget to look for the opposition effect: if you face away from the Moon, an apparent brightening around your shadow can often be seen.

The Buck Moon is named for the male deer that, during this time of year, are known for their seasonal antler growth. Other Full Moon names for July include Thunder Moon, Hay Moon, and our own Francine Jackson suggested Apollo Moon, in recognition of the first lunar landing in July 1969.

Neptune rises at about 23:00 in mid July (an hour later at the beginning of July, and an hour earlier at the end of the month). Located about 5° south of the Circlet asterism in Pisces (though the planet remains in Aquarius), it shines at magnitude 7.8. Tracking Neptune’s movement will be relatively easy as it appears within 10 arcminutes from 7.2 magnitude HD 221801, passing just 4 arcminutes south of the star on the 17th.

Uranus is a morning planet in July, rising in the constellation Aries at 01:00 (+/- one hour at the beginning/end of the month). You can spot its aqua-green, 5.7 magnitude glow within a triangle formed by similarly bright stars Pi, Omicron, and Sigma Arietis. The waning crescent Moon is nearby on the night of the 31st/August 1st.

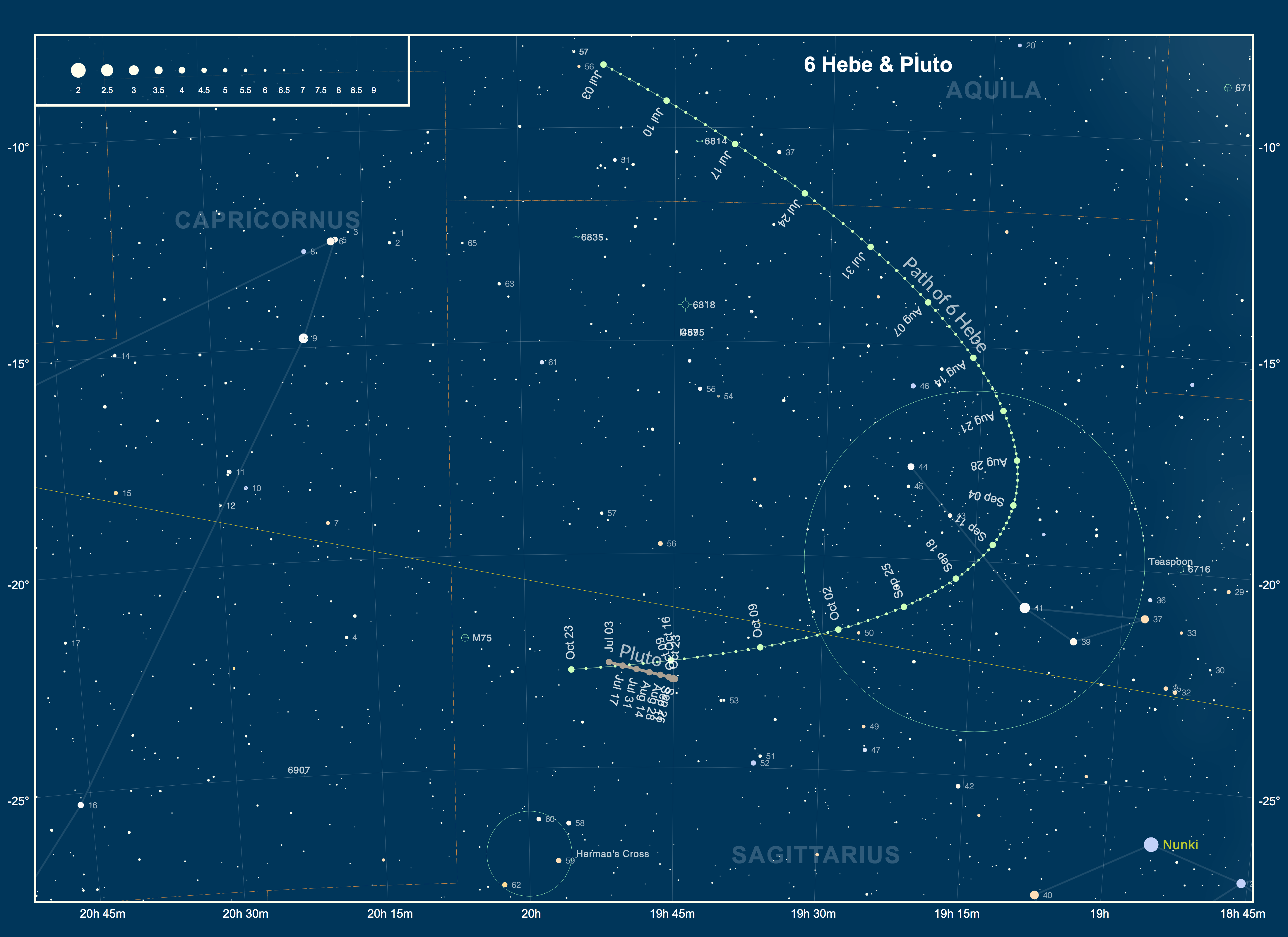

Asteroid 6 Hebe reaches opposition on July 17, and is closest to Earth on the 26th, at a distance of 1.260 AU. It shines as brightly as magnitude 8.3, visible in binoculars, in the star-rich fields of southern Aquila and northern Sagittarius.

Dwarf planet Pluto also reaches opposition on July 17. At a distance of 33.305 AU, Pluto doesn’t shine any brighter than magnitude 14.3, so you’ll need about a 12” telescope to spot it visually. It is located just 4° NNW of the Herman’s Cross asterism in eastern Sagittarius.

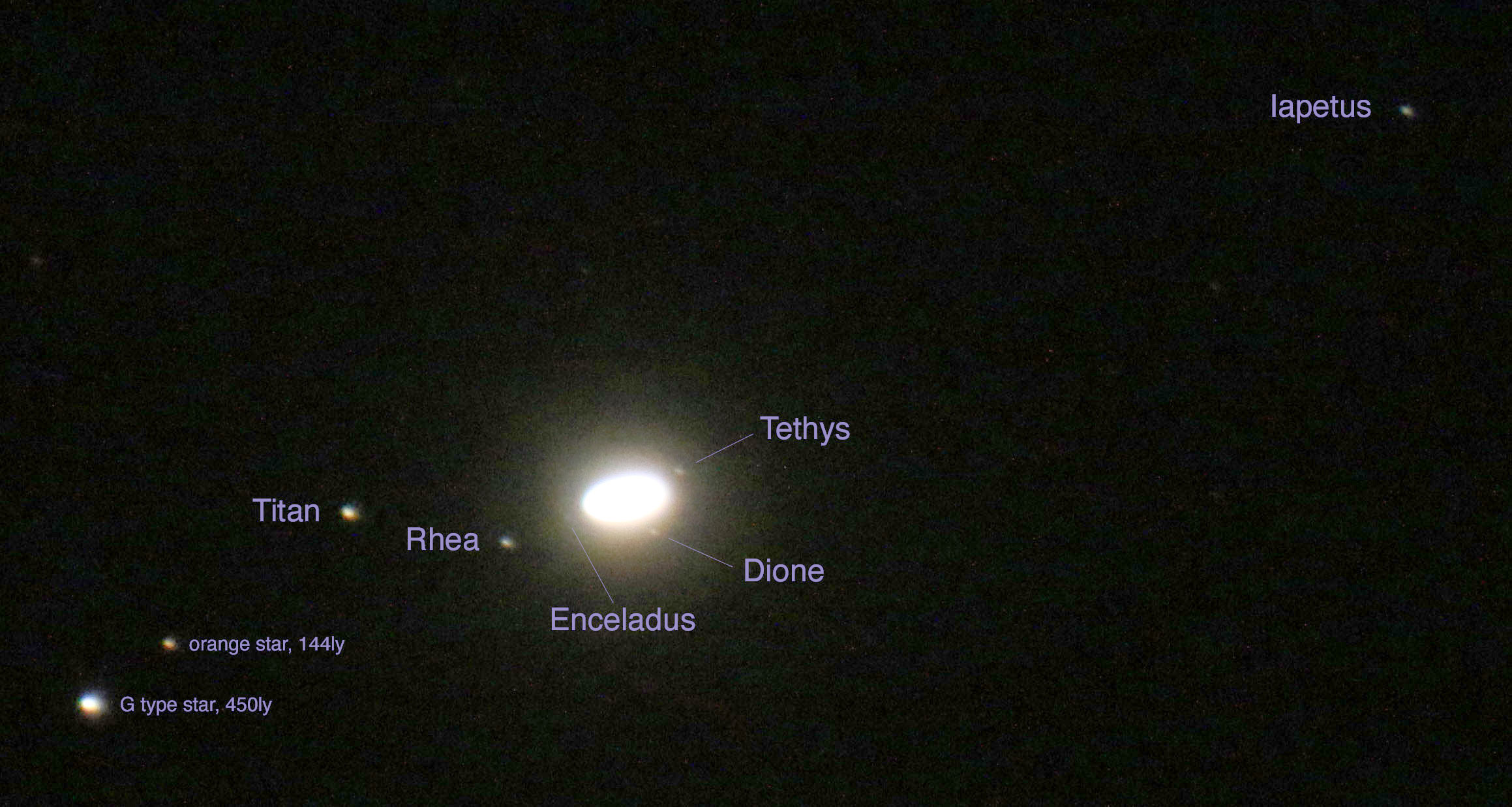

Observing Challenge: Iapetus

While you’re looking at Saturn, check to see how many of its moons you can see. Titan will be the brightest, at about 9th magnitude. Saturn has three mid-sized moons between 10th and 11th magnitude that are visible, and orbit inside of Titan. But there is another, more distant, mid-sized moon that isn’t always easily visible, Iapetus. Because Iapetus is tidally locked with Saturn, and it has, at some point in its past, swept up dark material on its leading hemisphere, leaving its trailing hemisphere somewhat brighter, it varies by as much as 2 magnitudes as it goes around its 79-day orbit around Saturn. We can see it more easily when it is on the western side of Saturn and moving away from us, which is where it is during early July. If you miss this opportunity to see the bright side of Iapetus, the next time it will be in this part of its orbit will be during mid-September.