November Sky Events

November 2017 :

Note: This article may contain outdated information

This article was published in the November 2017 issue of The Skyscraper and likely contains some information that was pertinent only for that month. It is being provided here for historical reference only.

Each day the Sun is setting earlier and earlier as we approach the northern hemisphere Winter Solstice on December 21. Amateur astronomers can begin observing immediately following suppertime. The skies of November are usually clear and transparent, allowing stargazers at every interest level to explore the heavens to best advantage. Today I’ll highlight a few sky events that will lure you out into the cool fall air to experience some astronomical delights.

First, many folks were confused that October’s full moon on the 5th was called the Harvest Moon instead of the Hunter’s Moon. This anomaly occurred because the Harvest Moon is the only full moon that derives its title based on astronomical circumstances. It is the full moon closest to the autumnal equinox—beginning of fall, which occurred back on September 22. Traditionally September is the full Harvest Moon.

However this year September’s full moon occurred on the 6th, 16 days before the equinox. Therefore, since the October 5 full moon was closer to the equinox, only 13 days after, it became the Harvest Moon…the first time since 2009. September became the full Corn Moon, another agricultural reference. So as best as I can determine, there was no Hunter’s Moon in 2017.

Fortunately the November 4 full moon name is not complicated. It is the full Beaver Moon, so named by Native Americans who harvested beaver pelts at this time of year for warmth during the long and cold winters.

During the first couple weeks of November the Earth will pass through a stream of debris left in orbit by Comet Encke. These often very bright yellow fireballs (meteors that explode and fragment into multiple pieces) comprise the Taurid meteor shower. The Taurids are fairly slow and enter our atmosphere at approximately 17 miles per second. You can expect no more than a half dozen shooting stars emanate from the sky in the constellation Taurus. To locate Taurus find the V-shaped pattern that defines the bull’s face, or locate the Pleiades — the Seven Sisters.

One very important “event” to note will occur on Sunday, November 5 at 2:00 a.m. That’s when we set our clocks back one hour as we return to Eastern Standard Time (EST) from Eastern Daylight Time (EDT). Everyone knows the phrase, “Spring ahead and fall back/behind.” Use that hour to catch up on your sleep!

Later that same day you’ll be able to observe the waning gibbous Moon pass in front of (occult) Taurus’ bright star Aldebaran. As the moon slides eastward (left) through the sky it will cover Aldebaran at around 8:03 p.m. along the Moon’s bright edge. While this event can be seen with the naked-eye, binoculars can provide a better view. However, a telescope with medium magnification will enhance the experience as the star slowly winks out behind the lunar profile. Aldebaran will reappear along the Moon’s dark limb at approximately 8:58 p.m.

On the mornings of November 12-14, early risers will see a conjunction (close pairing) of Venus and Jupiter only a few degrees above the eastern horizon during twilight. Venus will be the brighter of the two planets. They will be at their closest on the 13th, being well less than one full moon diameter apart. And on the 15th a very narrow waning crescent Moon may be visible about five degrees above the then separated Jupiter and Venus.

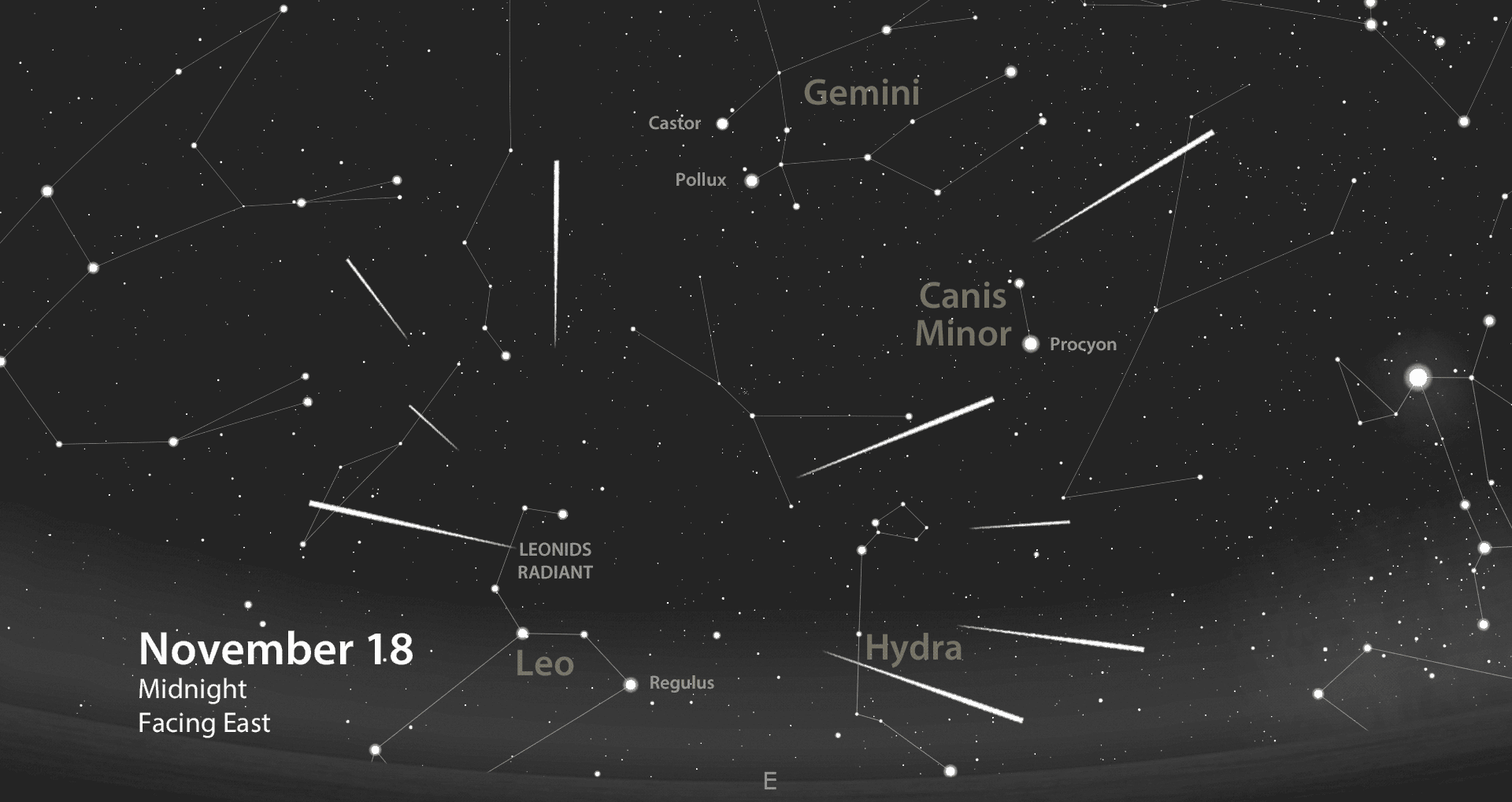

In addition, on the night of November 17-18, the peak of the annual Leonid meteor shower occurs. While this shower displays high numbers of meteors every 33 years, we are not close to one of those meteor storm years. Even though there will be a New Moon which won’t brighten up the sky, we can expect about 10-15 green or blue shooting stars per hour between midnight and dawn on the 18th.

The Leonids blaze across the sky at around 44 miles per second as they hit the Earth’s atmosphere nearly head-on. The resulting display produces many fireballs, with about half of them leaving trains of dust that can persist for minutes. The area of sky where the meteors appear to radiate from is in the Sickle (backwards question mark) asterism in Leo. Best of luck in seeing a handful of shooting stars.

And finally, if you’d like to get a glimpse of our solar system’s innermost planet Mercury, then give it a try during evening twilight on the 24th. It will be only 5-8 degrees above the southwest horizon, but it should be visible. Use Saturn, which will be about six and a half degrees above it, to locate Mercury.

Seagrave Memorial Observatory in North Scituate is open to the public every clear Saturday night. Ladd Observatory in Providence is open every clear Tuesday night. The Margaret M. Jacoby Observatory at the CCRI Knight Campus in Warwick is open every clear Thursday night. Frosty Drew Observatory in Charlestown is open every clear Friday night year-round.

Enjoy the crisp autumn weather as you explore the beauty of our universe.

Keep your eyes to the skies.