Pluto at Ninety: Discovered, Demoted, Visited

March 2020 :

A little more than ninety years ago, in a barred spiral galaxy named the Milky Way, a stellar system named Sol had a retinue of eight known planets revolving around it. The last one to be discovered was Neptune in September 1846. However, as time passed small perturbations in Neptune’s orbit were noted, which suggested another “trans-Neptunian object” existed whose presence altered his path around our Sun. It wasn’t until 1905 that a wealthy Boston astronomer, Percival Lowell, started a search for “Planet X” using his Flagstaff, Arizona, observatory. Lowell, with his mathematics background, and with the help of colleagues, tried to derive a possible orbit for a potential unknown planet. They even took photographic plates in 1906 of an area of sky where they thought planet “X” might be located, but with no results.

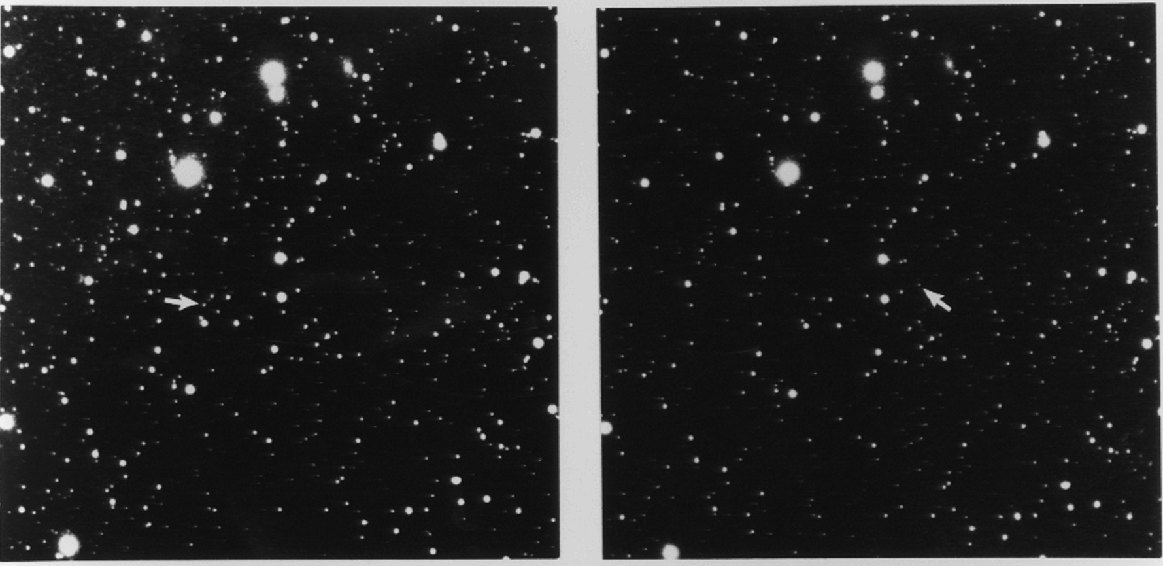

Unfortunately, Percival Lowell died at age 61 on November 12, 1916 and the search for the elusive “Planet X” ended. However, in 1929, the search for Pluto was resumed at the Lowell Observatory using calculations that Lowell had computed earlier. A 23 year-old Clyde W. Tombaugh was hired to meticulously image specific areas of the sky using photographic glass plates. The same star field would be exposed several days apart. Once the plates were developed, they were placed in a viewing machine called a blink comparator that held two plates. The operator could switch back and forth from one plate to the other. This process was called “blinking.”

Stars do not appreciably change position because of their vast distances from the Earth. However, an object within our solar system would show a slight shift in position given enough time had elapsed between the images. Many asteroids and comets had been discovered using the blinking process. An object in question would appear to jump from one position to another between the two images being compared. Making assumptions as to the possible distance to “Planet X,” and given the length of time between exposures, one could deduce from the movement of an object where it may reside in the solar system. Clyde was responsible for the entire tedious task of exposing, developing, and blinking the glass photographic plates.

Finally, on February 18, 1930, Clyde Tombaugh discovered Lowell’s distant world while comparing plates he had exposed on January 23 and January 29, 1930. As Clyde told Skyscrapers’ members when he visited Seagrave Observatory in 1987, until he informed his colleague Dr. C. O. Lampland across the hall from his office and then his boss Director V.M. Slipher, for 45 minutes he was the only person in the world who knew of the new planet’s existence. After careful re-examination of the data and confirmation by other astronomers, it was determined this newly discovered body was way out beyond the orbit of Neptune. The monumental discovery was announced to the world on March 13, 1930, the anniversary of Lowell’s birth.

“Planet X” was also given the more proper name Pluto, the Roman god of the underworld. (Naming astronomical bodies at that time adhered to Roman and Greek mythology.) And it is merely coincidence that the first two letters are Percival Lowell’s initials.

It is interesting to note that there was a link to Rhode Island in regards to Lowell’s search for what would become Pluto. My research as historian for Skyscrapers revealed that the former owner of our eight-inch Clark refractor and Seagrave Memorial Observatory, Frank Evans Seagrave, was a friend of Percival Lowell.

I do not know when Lowell and Seagrave first met, but from 1915 – 1917, when Seagrave was “working” as an assistant at Harvard College Observatory, it is apparent they had become fast friends. See this link for extensive details on the Percival Lowell/Frank Seagrave connection: http://www.theskyscrapers.org/the-conjunction-of-frank-seagrave-and-percival-lowell. In fact, one postcard from Seagrave to Lowell said in part, “Hope you will find X.”

After Lowell’s passing in 1916, Seagrave continued his correspondence with Dr. Slipher, the new Director of Lowell Observatory. In a postcard dated May 21, 1917, Seagrave wrote to Slipher stating, “If you should at any time find any conspicuous object that you think is “X” please send me some positions. Dr. Lowell many times promised me that I should be the first one to work on its orbit when discovered.”

Seagrave only found out about Pluto’s discovery through newspapers. Now 70 years-old, Seagrave hadn’t been asked to compute Pluto’s orbit as had been promised by his friend Lowell. Seagrave sent off several letters to Slipher in March and April 1930 reminding him of this arrangement, saying in one of them, “The last time I was with Dr. Percival Lowell was late in September 1916…He showed me his computations in relation to the outer Neptunian planet, and said to me, ‘Seagrave, if the Lowell Observatory is the Observatory that will first find this planet, you will be the first one to compute its orbit.’ No writing to this effect. Only a verbal statement…”

Eventually Slipher responded to Frank Seagrave (very diplomatically of course). Briefly stated, Slipher wrote, “it seemed to me that we here should determine for it a preliminary orbit. This because it seemed best for Lowell Observatory to find it out and make it known if the object were thus shown to be less important than it had appeared. Dr. Lowell and the Observatory had put so much into the problem as to appear to justify this policy.” He went on to say, “I hope you will feel that we have tried to be fair. We of course realized at the outset that you who compute orbits were better equipped to do such work, but the reasons given above decided our course.”

Over the ensuing decades there was a limit to what information could be learned about so distant a world. On January 19, 2006, the New Horizons spacecraft was launched on its almost 10-year journey to explore icy planet out in the depths of our solar system.

In the meantime, other bodies beyond Pluto had also been more recently discovered, and astronomers wanted to classify these objects. During a meeting of The International Astronomical Union (IAU), an association that governs such things, decided to modify the definition for a planet. Under the new parameters Pluto no longer qualified as one. A new term, dwarf planet, was introduced. This reclassification became official on August 24, 2006 and Pluto was kicked out of the planet club.

Pluto’s status may have changed, but the New Horizons spacecraft mission to explore Pluto and its moons didn’t. After a 9.5-year journey New Horizons had a brief encounter with Lowell’s “Planet X,” cruising by this dwarf ice-ball of a world at 30,800 miles per hour, coming within 7,750 miles of its surface. Astronomers learned more from this close encounter than they had since Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto in 1930. If you’d like to read about New Horizon’s discoveries, please check out this link: https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/newhorizons/main/index.html

Although Clyde Tombaugh died on January 17, 1997, at 90 years-old, before New Horizons’ launch and before Pluto had been demoted to dwarf status, a part of Clyde made the epic journey to explore this distant world. Upon Tombaugh’s death he was cremated. An ounce of his ashes was put in an aluminum container and placed onboard the spacecraft. The container’s inscription reads in part, “Interred herein are remains of American Clyde W. Tombaugh, discoverer of Pluto…”

While Pluto is merely a tiny speck as seen through the largest of the telescopes in Rhode Island, there are many other more prominent celestial objects to view that will impress you with their beauty. Let the volunteers at all the Rhode Island observatories help you explore the heavens during free public open nights.

Keep your eyes to the skies.

Pluto discovery plates taken on January 23 & 29, 1930. Lowell Observatory archives.