The 30-Year Legacy of NASA's Remarkable Spacecraft: The Space Shuttles

August 2011 :

It was a different time and a different world. Ronald Reagan was recently sworn in as President of the United States. Return of the Jedi was yet to be released. Video game enthusiasts were playing Asteroids and Pac-Man. I had never seen a computer, nevermind having used one. My first gaze through a telescope was still three years away. But way down south in Florida, a state with which I became familiar just a year prior, a magnificent white spacecraft roared towards the sky over a huge plume of smoke in an iconic image that would grace the covers of National Geographic and Time magazines, among many others.

Back in those days, we had three television stations to choose from, and if the weather was good, one or two more could be watched through the “snow.” But despite a lack of variety on the television dial, a Space Shuttle launch was worthy of interrupting the regularly scheduled programming, and I vaguely recall watching three or four launches in the early 1980’s. I do not recall if I witnessed STS-1 Columbia or not, but I recall being fascinated as I listened to the NASA commentator calling out altitude and distance every few seconds following liftoff, finding it incomprehensible how quickly the shuttle zoomed away from its launch pad as the grainy image of the huge rocketship was reduced to a bright dot just after the solid rocket boosters separated. The television camera stayed right with it all the way until main engine cutoff, at which time the commentator would declare that the astronauts were now in orbit.

While I was fascinated with the launches I had seen on television, I wasn’t old enough to really appreciate what it was that I was witnessing, what the space shuttle was all about, or know anything about the people who flew it. In my mind, the space shuttle had always been flying, because I had no recollection of what happened before.

During the same time period, Voyager images of the planet Saturn, its rings, and moons began to make their way into my consciousness, which I began to take a strong interest in. I read as much as I could about Voyager, and found out about its Jupiter flyby a couple of years earlier. I learned that Voyager’s next planetary flyby wouldn’t come until January 1986, which was forever in the future to me at that time. I continued to read and learn about past manned as well as unmanned space exploration. I had recollections of being aware that men had walked on the Moon, but was still more engaged by the prospect of unmanned spacecraft exploring deep into the solar system.

I had watched a few Space Shuttle launches, but had more or less taken them for granted and didn’t pay much more attention to the shuttle flights. Besides launches and landings, information about what the astronauts actually did on these spaceflights was hard to come by in the pre-internet era.

By mid-decade, the buzz about Halley’s Comet had gone full-steam, and being equipped with a telescope and rapidly expanding interest in the solar system, I was determined to see it. I didn’t have much access to the night sky besides the northwestern horizon over the lake, which actually extended from west-southwest all the way to north-northeast. I had began to learn the constellations--at least the ones I could see given my limited sky--with the hopes of finding the comet.

Then there was the excitement of Voyager 2 finally making it to Uranus. January 24, 1986 had been marked on my calendar since the early 80’s, even though I knew it would be several weeks before I would see the pictures beamed back from the venerable little spaceprobe.

Then it happened.

The morning of January 28, 1986 would become my generation’s “where were you when” moment. Space Shuttle Challenger and its seven brave astronauts never would complete their flight on mission STS-51L. I was in the sixth grade at W.L. Callahan School in Harrisville and had just come back from lunch recess when the news came across the intercom. The lights in the classroom were turned out and the school observed a moment of silence. I didn’t see the launch until later that evening on the news. Somehow it was unimaginable that a Space Shuttle could take off but never land. Then we listened to President Ronald Reagan give his memorial speech. A somber moon permeated everywhere. How could this happen? Will we ever fly again?

While Challenger never reached orbit on her final flight, STS-51L was able to accomplish something that no Space Shuttle flight before it had done. For the first time I realized the significance of human spaceflight and why it was important.

Within a day or two I had memorized the names of all the astronauts on STS-51L and created a memorial piece for art class. I closely followed the news reports with the curiosity of an engineer as the investigation pieced together what went wrong.

I found a copy of Space Shuttle Operator’s Manual and read it cover to cover, which greatly deepened my understanding not only about how a spacecraft works, but also how unique the Space Shuttle is and what it is capable of.

Months went by, and I eagerly anticipated the return to flight. During my rapidly expanding interest in astronomy and space exploration I had come across information about the Hubble Space Telescope, the deployment of which had been delayed by the Challenger accident. This was the first direction connection between the Space Shuttle and my interest in astronomy that I had become aware of. After following the Voyager missions for several years, I looked forward to what an observatory placed outside of Earth’s atmosphere could accomplish.

I occupied the hiatus in Space Shuttle flights learning even more about the history of spaceflight, including the adventures to the Moon that had taken place a few years before I was born. It was during this time that I learned about Apollo I, and how Apollo XIII nearly ended in disaster.

When it was finally time to fly again, I wasn’t able to watch the launch live on television, but I recall sitting in social studies class thinking about the return to flight, drawing pictures of Discovery blasting off on STS-26. All was right again. We were safely flying and landing Space Shuttles once again.

I made an effort to watch as many launches and landings as possible, something that would become a mainstay of my interest in spaceflight right through STS-135 which touched down on July 21 of this year. It was easy to track Space Shuttle flights in the early days and even during the return to flight era of the late 1980’s, when the major television networks would broadcast them live.

As time passed, however, public enthusiasm for spaceflight waned again but my personal connection to it would not. Television networks soon would not bother interrupting normal program to show a Space Shuttle flight, but by this time I had access to cable television and could always find CNN to show me at least the first two minutes of a launch. It remained elusive, however, to track mission details in real-time other than launches and landings. I would learn of the exploits of the astronauts in newspaper and magazine reports published days, weeks, or in some cases, months after the fact.

The public’s attention would soon turn to NASA once again, however this time in a decidedly negative manner. Shortly after the long-awaited deployment of Hubble Space Telescope by deployed by Discovery during STS-31 mission, it was found that the orbiting observatory’s mirror had been made to the wrong figure, rendering the entire telescope nearly useless. Having read Richard Berry’s Build Your Own Telescope a year or two earlier, I had a good idea of what it takes to refigure a Newtonian telescope mirror. I had thought, if HST’s mirror could be brought back to the ground, something only the Space Shuttle could accomplish, the telescope’s optical flaw could be corrected.

As it turns out, repairing the telescope was possible, even without bringing it back from orbit. With the remarkable capabilities of the Space Shuttle, spacewalking astronauts performed repairs by means of swapping components on board the telescope to correct the optical flaw. Among replacing other components on the telescope, a package called COSTAR was installed by spacewalking astronauts on Endeavour’s STS-61 flight. One of the astronauts that worked on the first Hubble repair mission, Story Musgrave, would visit Skyscrapers during AstroAssembly 2005. I would also later learn that my friend Phil Rounsville from the Amateur Telescope Makers of Boston had worked on some of the components of the COSTAR package. Phil was the first person to introduce me to Skyscrapers and Seagrave Memorial Observatory for AstroAssembly 1995.

As someone who grew up with the Voyager missions, I had grown very enthusiastic about unmanned missions to other planets in the solar system. During the mid 1990s, the Magellan mission to Venus and Galileo mission to Jupiter vastly enhanced our knowledge of these two planets. Both of these space probes were launched from the payload bay of Space Shuttle Atlantis back in 1989, not long after the post-Challenger return to flight and just before the deployment of Hubble. Within two years, Space Shuttle Discovery deployed the Ulysses mission, which left orbit to observe the Sun, and Atlantis deployed the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, the second of NASA’s Great Observatories program (Hubble being the first). It would turn out that the period from 1989 to 1991 was the most prolific time for the Space Shuttles’ contribution to astronomical research.

The next era in Space Shuttle flights would be the first time since the closing days of the Apollo program that a joint American-Russian mission would take place. In fact there were nine Space Shuttle flights in total that would dock with the Russian Mir space station, which had been in orbit since 1986. Space Shuttle Atlantis became the workhouse of the Shuttle-Mir program, which lasted from 1995-1998. Even despite potential safety concerns following a fire on board Mir and its collision with a Progress resupply vehicle, the Shuttle-Mir program continued. This would become a signal of international trust and cooperation that would later be essential for the construction and operation of the International Space Station.

It was during the Shuttle-Mir program that I first sighted a Space Shuttle directly. In 1996, long before the days of heavens-above.com and its Space Station visibility tables, I happened across some information that listed the dates and times for a series of Shuttle-Mir pass over Rhode Island. I spotted Atlantis and Mir docked with the naked eye, and was able to track them for a brief moment using my 10-inch SCT.

I do not recall when NASA begin offering a live web stream, but I began watching it sometime around the turn of the millennium. It was a fairly low resolution view, given that high bandwidth connections were still rather uncommon. It didn’t matter as I could not receive the broadcast via cable TV, and I wanted to see the whole eight plus minutes of a launch, all the way to MECO, rather than a minute or two of them.

The next few missions would be the early assembly missions for the International Space Station, an ambitious and long-term project that was one of the original design goals of the Space Shuttle. Lifting large modules into orbit, hoisting them out of the payload bay and maneuvering them into precise connections with the remote manipulator system’s Canadarm, and providing a workstation for spacewalking astronauts doing all of the “finishing touches” was all well within the capabilities of the Space Shuttle.

One Space Shuttle flight I would watch launch, but not land. I recall watching the launch of STS-107 Columbia on my birthday in 2003. Sadly, this would become the final flight of the first Space Shuttle.

Following Columbia, however, we were treated with additional camera views and maneuvers that would make watching Space Shuttle flights even more enjoyable. The cameras were added to the twin solid rocket boosters and the external tank. The purpose of the cameras was to ensure the integrity of the orbiter’s thermal protection system during ascent.

Even the very first return to flight, Discovery’s astronauts performed the first-ever repair of a Space Shuttle orbiter in flight. It was not a major repair, but mission managers thought it wise to pluck a couple tabs of gap filler that had protruded from between thermal protection tiles under Discovery’s nose. This maneuver made for an interesting spacewalk to watch as it gave never-before seen views of an orbiter in flight, but it also helped train that astronauts for this type of procedure should it become critical.

It had also been decided that the Space Shuttle would no longer fly to destinations other than the International Space Station, so that the ISS could provide an emergency quarters for a shuttle crew should the orbiter be deemed unfit for reentry while in orbit. From now on, heat shield inspections would become a regular part of the Space Shuttle flights. One would be performed during the first full day in orbit, and one was usually performed the day after undocking from the ISS.

Additionally, the r-bar pitch maneuver, also known as the RPM, or “backflip” was added to the Space Shuttle’s approach procedure. The Space Shuttle would maneuver to a station-keeping position immediately “below” the station while performing a minutes-long backflip maneuver so that astronauts and cosmonauts on the space station could photography the complete underside of the orbiter. What was an essential heat shield inspection became one of the most interesting spectacles of the entire Space Shuttle flight, as NASA TV would nearly always broadcast this maneuver. Watching the Space Shuttle pitch up and over a complete 360 degrees while Earth passes by beneath was always one of the key events I was sure to watch, along with launch and landing. The maneuver took place about 20-30 minutes before finally docking to the ISS.

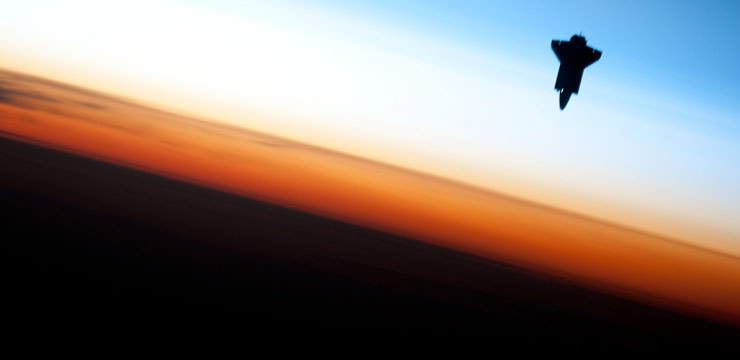

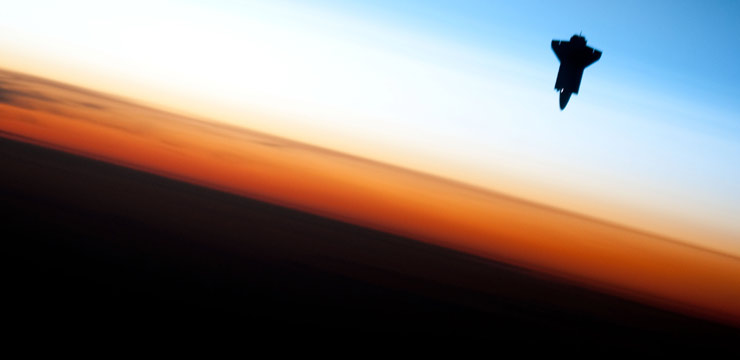

The post-undocking flyaround was also a key event. This maneuver involved the Space Shuttle flying a complete loop around the ISS in order to document the construction progress as well as to check the condition of exterior components. From the station’s perspective, however, this provided another opportunity to see a Space Shuttle in “free flight,” again with amazing background scenery.

During the last few missions, NASA TV had finally upgraded the quality of their broadcast to a high definition stream. This was a vast improvement to the previous stream, which had been sub-standard definition. NASA also began sharing a lot of “behind the scenes” segments via their YouTube channel (NASATelevision). Learning more about the processing, procedures, and the people who put it all together gave me even more appreciation and enthusiasm for the Space Shuttle program, even knowing now that the program was nearing its premature end.

Atlantis’ STS-125 flight was the first Space Shuttle flight that I followed continuously. This ambitious flight would become one of my favorites, as this would be the final time the Space Shuttle would be sent to upgrade and repair the Hubble Space Telescope. This mission was scratched after the loss of Columbia due to the requirement for all flights to dock with the ISS.

Astronauts performed five spacewalks and accomplished all of their tasks to send Hubble off for another several years of service. As part of this mission, the wide-field planetary camera 2 (WFPC2) which was installed during the STS-61 mission, and famous for many of Hubble’s most well known images, was returned to Earth and will be displayed at the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum. This is the most significant piece of Hubble that future generations will be able to see as there are no plans to retrieve the entire telescope at the end of its service life. If there could be just one more Space Shuttle flight, I would like to have seen a HST retrieval mission, as I regard the orbiting telescope as the most significant hardware serviced by the entire Space Shuttle program. No other satellite or space probe has generated as much public interest in space and astronomy than the venerable Hubble Space Telescope.

The second-to-last flight of the Space Shuttle, STS-134, saw Endeavour deliver the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer to mount to the space stations’ truss. This particle physics experiment will investigate the basic building blocks of the Universe.

The final flight, STS-125, would bear no special payloads or mission objectives other than a fairly large space station resupply. However, the public attention given to Atlantis during this flight would suggest otherwise. Other than the nine tons of supplies for the International Space Station, this final flight carried with it, as all flights had done for a generation, the hopes, dreams, and inspirations of all who appreciate the efforts of exploring the Universe.

Thinking back on something that had been a part of my life as long as I can remember, it becomes apparent that the Space Shuttle was far ahead of its time. We asked it to do a lot, and in its 135 flights it accomplished everything we asked of it and more. It certainly could have done a great deal more if the program were to continue. But unfortunately its story is how history and it saddens me to think of it as such. The orbiters are being dismantled so that they can be made safe for permanent static display in museums. Perhaps I will get the chance to see Atlantis, Discovery, or Endeavour in person someday, but like seeing an old airplane in a museum that you know will never fly again, it just won’t have the same feeling as watching them perform their duties in space via NASA TV, or even watching its starlike presence floating silently across the sky. One thing is for certain, the Space Shuttle program will receive its due respect in the history of great spaceflight achievements just as Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo have.

Related Topics