Tardigrades: The Hardiest Little Organisms

November 2017 :

I can remember several years ago hearing of a television show that stated that, were man to be wiped out, the next primary civilization would be cats. Looking at mine, it terrifies me that they could actually take over the Earth; however, the real heads of our planet, the ones we should try to emulate, specially if we want to travel off the planet, are most likely the “cutest” little animals ever found, tiny tardigrades. These hardy creatures have been known to exist in and on places we could only dream of: buried in a time capsule in Norway (they were fairly dried up, but still alive), frozen to one degree above absolute zero, even hitching a ride on the outside of an ESA space craft.

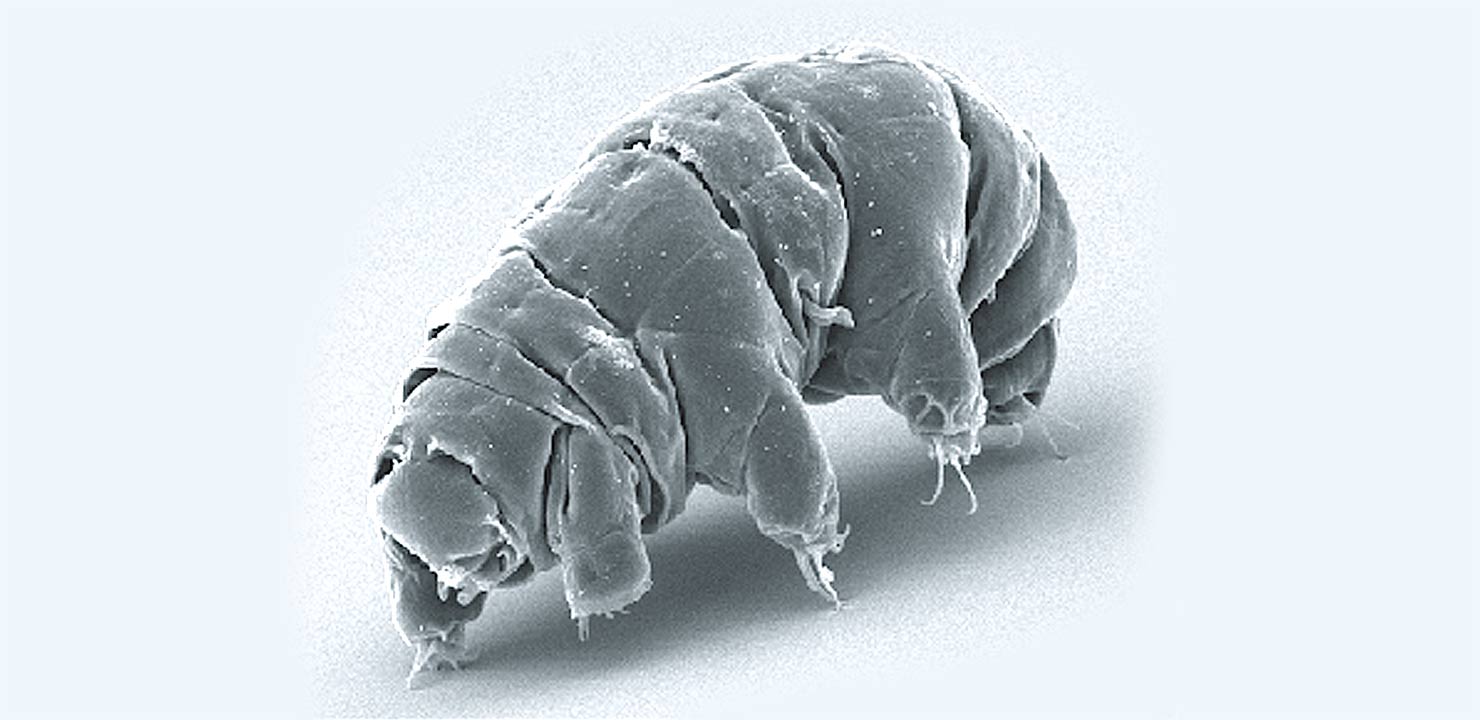

What gives these adorable little animals, often nicknamed water bears, this superpower ability has been suggested to come from a unique accomplishment: DNA theft. It appears approximately one sixth of their own DNA has come from other organisms, mainly bacteria. This apparently occurs, courtesy of one major study, through a process called horizontal gene transfers, seemingly common in bacteria and other tiny microbes. If other animals can possibly exist in environments totally lethal to large organisms (such as us), it appears tardigrades can, and much better. In fact, their incredible survival occurs because of their amazing ability to adapt: They can exist without water by replacing it with a sugar called trehalose; they are so small (about 1.5 millimeters long) they can easily hide from predators; their teeth are so sharp, they can spear algae and other tiny animals; plus, they have been here longer than almost any other animal on Earth. Some of you might recall even Neil deGrasse Tyson enjoyed speaking of them on his COSMOS: A Spacetime Odyssey several years ago. If only mankind could learn some tricks from this minianimal. It would make the possibility of space travel so much easier.

SEM image of Milnesium tardigradum in active state. Schokraie E, Warnken U, Hotz-Wagenblatt A, Grohme MA, Hengherr S, et al.