The Precession of the Equinoxes

March 2016 :

One of the problems in trying to introduce the public to the sky is having the North Star, Polaris, so “dim.” It’s been written about, sung about, and traditionally treated as if it should be a beacon brighter than anything else overhead. But, for those who are fairly disappointed, don’t despair: In only 13,000 years, we should be sailing the seas by the light of Vega, the brightest star of Lyra, the Harp.

The understanding of why this will happen isn’t new; in fact, Hipparchus suggested changes were happening in the sky over two millennia ago. But, of course, the infamous question is why? What brings the sky to such an occurrence? And, for us oldsters, reverting back to the 1970’s hippie revolution, what does that have to do with the Age of Aquarius?

The Earth is inclined about 23½ degrees from the vertical, believed in part to be a result of the Earth’s interaction with a Mars-sized body, which propelled material from our early planet. Though much of that material returned to Earth, the particles that didn’t fall back coalesced into our neighbor satellite. This interaction also resulted in the Earth undergoing the tilt that is still a part us today.

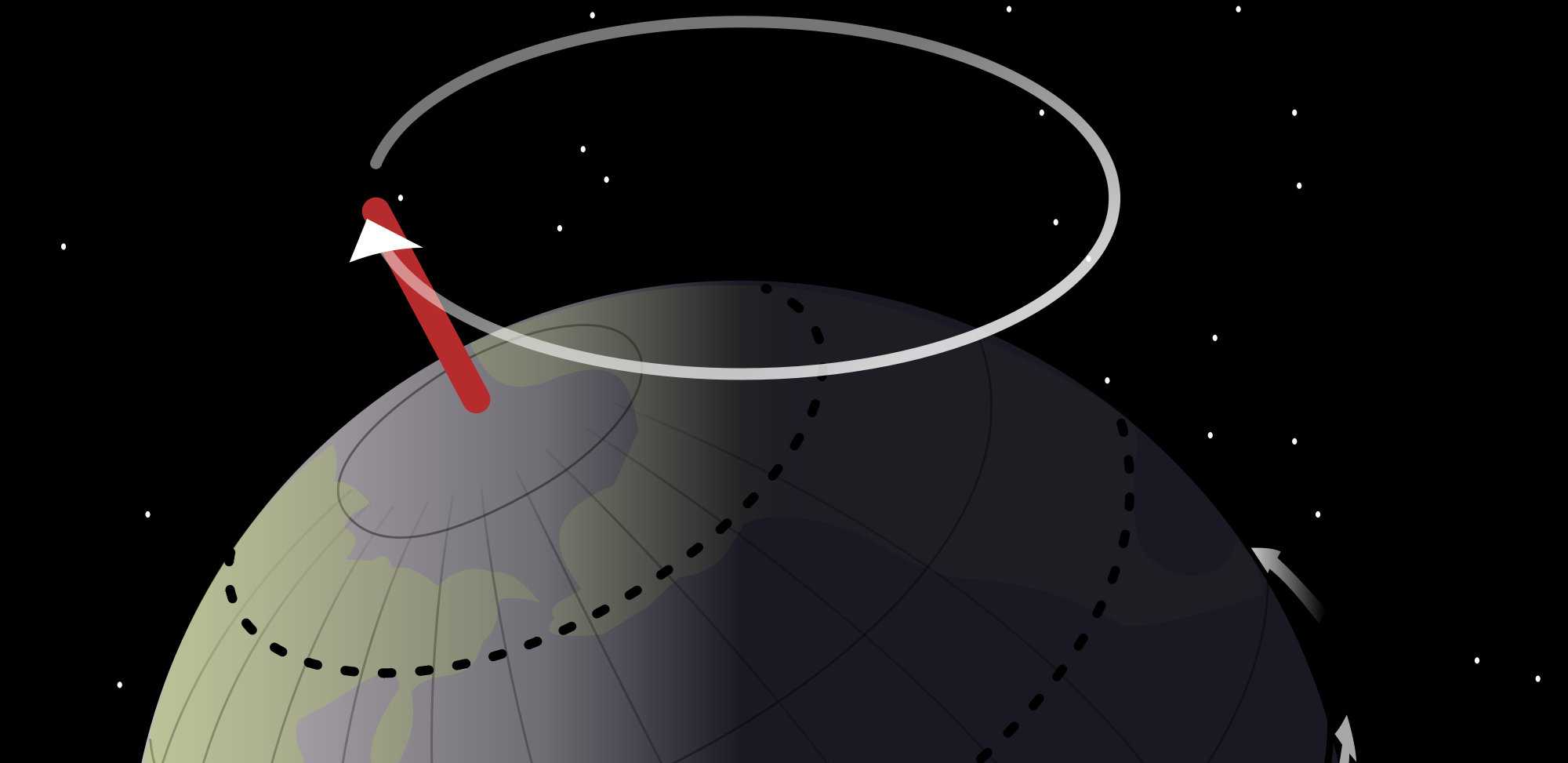

Most importantly for us, the Earth’s tilt is responsible for our seasonal change; without it, we would have virtually the same weather conditions all year-round. However, that 23½ degrees, though constant, doesn’t just stay in the same place at all times. Like a top, or a coin being spun, the orientation of the Earth slowly moves around, creating an approximate 47-degree circular movement with respect to the vertical. For the Earth to undergo this entire motion takes just under 26,000 years. Therefore, in a human lifetime, the change occurring overhead is negligible, just seconds of arc. But, looking backwards, some of you might recall learning of the historic time frame, thousands of years ago, when Polaris, which is at the end of the Little Dipper’s handle (or Little Bear’s tail), wasn’t the North Star, as it is today; instead, it was Thuban, part of the body of Draco, the Dragon.

The locations of the celestial north (and south) pole positions aren’t the only noticeable points. We have astrology to thank us for reminding us of this. Thousands of years ago, when the horoscopes were created, they were done so with respect to the position of the vernal equinox, the intersection of the celestial equator (ours extended to the sky) and the ecliptic (the Sun’s apparent path across the celestial sphere) as the Sun appeared to travel from below the celestial equator to above it. This gave us longer daylight periods, and hence, more sunlight to warm the Earth, allowing the beginning of the planting season – spring. It was noted that where this intersection was located was within the region of the constellation Aries, the Ram, the so-called “first point of Aries.”

However, as thousands of years have gone by, the process of precession has moved that intersection point to Pisces, the Fishes, making all our astrological signs off by one. And, to make matters worse, that vernal equinox point is now low within Pisces, ready to move again, into the next constellation in line, Aquarius. Although it will be several hundred years before the actual change occurs, you might want to dust off your tie-dyes and get your flower gardens ready for the next major change in the astronomical (and astrological) settings. Oh, and start growing your hair – it will need to be “shining, gleaming, streaming. . .” et al.

However, as thousands of years have gone by, the process of precession has moved that intersection point to Pisces, the Fishes, making all our astrological signs off by one. And, to make matters worse, that vernal equinox point is now low within Pisces, ready to move again, into the next constellation in line, Aquarius. Although it will be several hundred years before the actual change occurs, you might want to dust off your tie-dyes and get your flower gardens ready for the next major change in the astronomical (and astrological) settings. Oh, and start growing your hair – it will need to be “shining, gleaming, streaming. . .” et al.

In addition, as the location of the Sun at the different positions will change, so will the times we will be observing our seasonal constellations. In one-half the precessional time, about 13,000 years, we will not have to freeze to enjoy what some consider their “favorite” star pattern, Orion, the Hunter. Instead of being our sign of winter, Orion will reign during the warm, summer months. And, Vega, long part of our summer sky, will be the closest star to the north celestial pole, still not the brightest, but much more so than Polaris, and easier to direct the public toward the direction north.